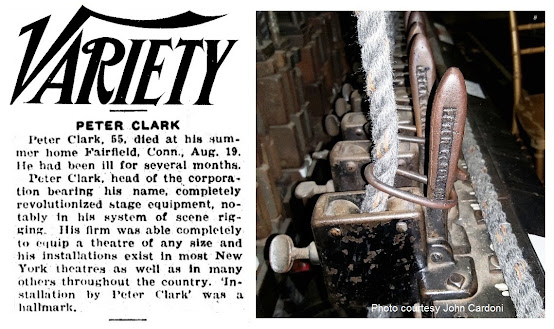

Upon his death in 1934, Variety wrote that Peter Clark "had completely revolutionized stage equipment." His name (right) was emblazoned on an estimated 15,000 Peter Clark counterweight system locking handles installed from coast to coast.

The following decade is a blank, and not until Peter Clark was twenty-nine years old did he first appear in print, below. There is no information as to the identity of Hugh Lavery or why Peter Clark split with him. In subsequent ads, the starting date of Clark's shop is variously listed as 1902, 1904, 1905 and 1906.

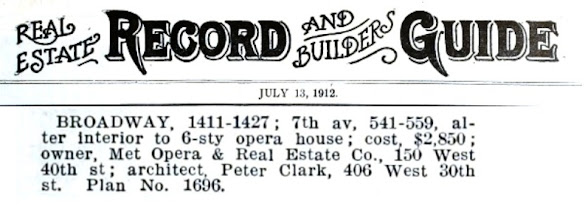

By 1912, Peter Clark was performing work for the Metropolitan Opera Company as well as the Metropolitan Opera & Real Estate Company, who owned the building.

In his first known press write-up, Peter Clark is credited for building the stage at the new Havana Opera House (1915)-- and also for building the stage at the Met and the Hippodrome.

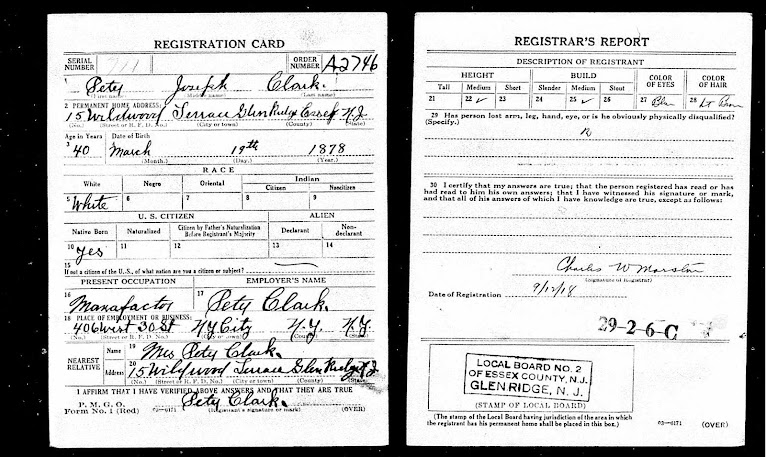

His 1918 draft registration reveals his full name to be Peter Joseph Clark; that he had blue eyes; light brown hair; and was of medium build and height.

Besides making new theatres, for thirty years Clark worked without cease in the creation of effects for Broadway shows (and the Met opera) yet there is virtually no record to show it. In theatrical parlance, Peter Clark was the "head carp" for New York City, called upon to make the impossible possible, and there was no one he didn't work for. An example of a Clark effect is shown below, From the Crosby Clipper, house organ for the makers of Crosby clips, December 1917.

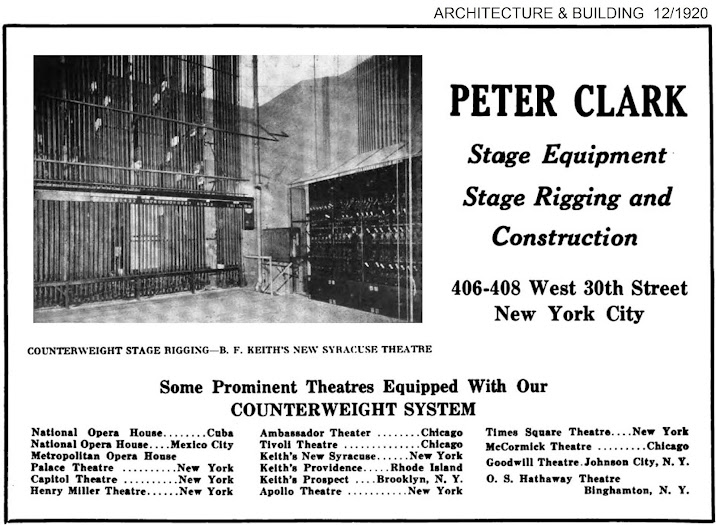

Clark's second ad, ten years after the first, featured the Peter Clark counterweight system. Evidence suggests that the Palace Theatre (Broadway, 1913) was his first system installation, but Clark's first documented installation was four years later at the Broadhurst (also Broadway, 1917). Below, the 1918 Chicago Pantheon Theatre. For an HD view, click here.

One year later, same ad, different theatre pictured: Keith's Fordham (The Bronx, 1921).

Another view of the Hillstreet.

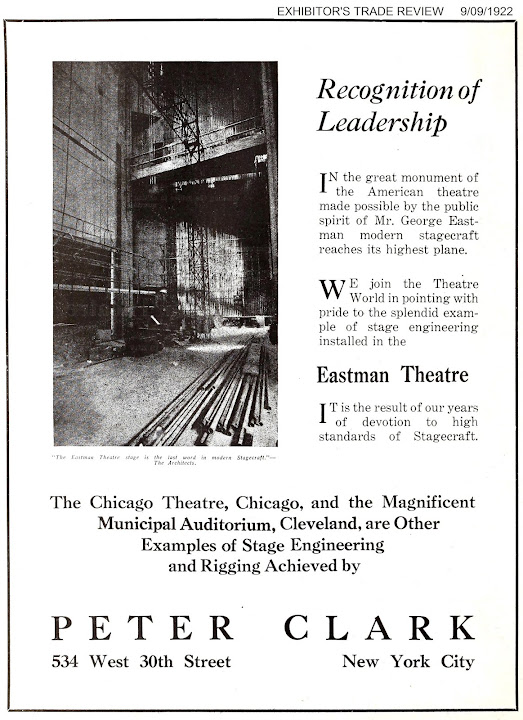

The Eastman Theatre (Rochester, 1922).

The Harris Theatre (Chicago, 1922).

A closer look at the Harris rail, which included linesets for side tabs, marked "ST." at center.

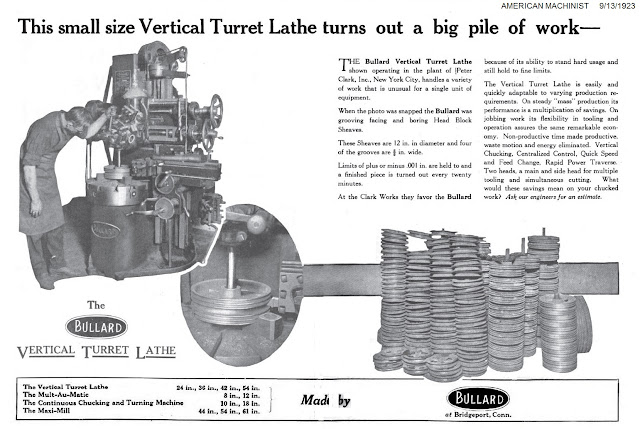

An advertisement for Bullard's lathe featuring the only known photographs of Peter Clark's shop. For a larger view, click here.

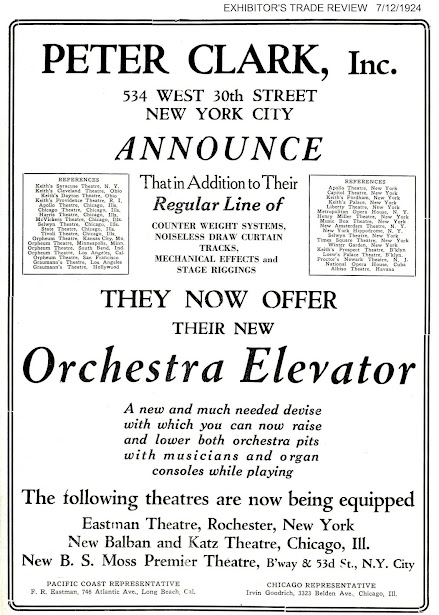

Clark's new orchestra pit elevator was first installed at the Eastman; the Chicago Uptown Theatre (1925); and the B. S. Moss Colony (1924), later known as the Broadway Theatre.

Broadway was the Great White Way, and Peter Clark equipped almost all of the Broadway legit and movie houses. The Colony was located adjacent to the 53rd Street elevated, and a block north was the Hammerstein, also Clark-equipped, later known as CBS Studio 50.

The Eastman Theatre was equipped with elevators in a 1924 renovation. Over the next ten years, Clark would install over two hundred lifts in one hundred theatres. To see an installation list by town, click here.

The first Peter Clark ad (1910) makes no mention of his counterweight system, so presumably it had not yet been invented.

In his first known press write-up, Peter Clark is credited for building the stage at the new Havana Opera House (1915)-- and also for building the stage at the Met and the Hippodrome.

Besides making new theatres, for thirty years Clark worked without cease in the creation of effects for Broadway shows (and the Met opera) yet there is virtually no record to show it. In theatrical parlance, Peter Clark was the "head carp" for New York City, called upon to make the impossible possible, and there was no one he didn't work for. An example of a Clark effect is shown below, From the Crosby Clipper, house organ for the makers of Crosby clips, December 1917.

Unquestionably, Peter Clark's greatest legacy to show business was the invention of a safe and practical counterweight system, after which all others have been copied. Before counterweight systems, scenery was flown from wooden battens suspended from hemp rope and counter-balanced by sandbags. The terrible Iroquois Theatre fire of 1903 was blamed in part of faulty and flammable rigging and prompted new codes. The time was ripe for a completely fireproof system.

Prior to Peter Clark's breakthrough, counterweight installations in the United States were a rarity and reserved for grand opera. The Chicago Auditorium (1889) was the first, followed fourteen years later by the New York Metropolitan (renovation, 1903), and the Brooklyn Academy of Music (1908). Below in an undated photo, the Met's flyrail can be seen to the far right.

Loft blocks which could slide along the gridloft deck, rather than the overhead stationary wheels of Chicago and the Met, facilitated rapid re-spacing of sets, and mule blocks allowed for curved upstage cyc pipes and side tabs, typical in many Clark installations.

Loft blocks for fire and house curtain at the Broadhurst Theatre (Broadway, 1917) the oldest documented Peter Clark counterweight installation. Clark's name can be seen on the gray wheel.

Clark's components were harmonious and smooth-cornered, designed rather than "pulled from stock," a system so safe and simple that even school boys could enjoy it. Clark standardized the size of the pipe batten at 1-1/2" I.D. and all lighting gear adapted to it.

Within a dozen years of its inception, Clark's system had become the industry standard, with hundreds of documented installations from coast to coast. To see a list by town of the three hundred twenty-five jobs, click here.

For reasons lost to time, neither the Peter Clark system nor its component parts were patented by Clark. Perhaps for that reason, the United States Institute for Theatre Technology (USITT) believes that a stage hardware supplier in upstate New York invented the modern counterweight system. Yet in a rare print ad from 1929, J. R. Clancy makes no such claim.

In stark contrast, the obituaries for Peter Clark tell a different story. The New York Times credited Clark as inventor of "revolutionary stage devices"; the Herald Tribune stated that "Mr. Clark perfected the elaborate system of counterweights [which] banished. . .clumsy backstage sandbags"; the Motion Picture Herald noted that Clark's "development of counterweights vastly simplified the problems of scene shifting;" and Variety wrote that Clark "completely revolutionized stage equipment, notably in his system of stage rigging."

Prior to Peter Clark's breakthrough, counterweight installations in the United States were a rarity and reserved for grand opera. The Chicago Auditorium (1889) was the first, followed fourteen years later by the New York Metropolitan (renovation, 1903), and the Brooklyn Academy of Music (1908). Below in an undated photo, the Met's flyrail can be seen to the far right.

Rather than loft blocks, wheels mounted on a shaft were a feature of houses such as the Chicago Auditorium, shown below. The head wheels were grooved both for the pickup cables and the operating line, a first.

Cumbersome in operation, these layouts lacked a locking rail and the design necessitated that weights could not be loaded from the front. These arbors rode on two tracks, inner and outer, and outer track blocked access to the weights.

As late as 1918, a patent was granted for such an awkward arrangement.

Before Clark, the only patented scenic rope lock was worked with a steering wheel.

Peter Clark not only modernized, he revolutionized. The sleek appearance of his locking rail was stylishly industrial, neat and numerical, and a far cry from the chaotic coils of hemp. Introduced about 1917, the Peter Clark system was not only labor-saving, but fireproof, with steel cable instead of flammable rope pickups; iron stage weights for sandbags; and a rail (with locks!) at stage level which eliminated multiple overhead fly galleries. Eight Clark inventions combined to create an entirely new and unified design, as shown below. For a larger view, click here.

To see a Peter Clark fly system in action, click here.

A quote and specification for a Clark system in 1929, signed by Peter Clark himself. To see a larger view, click here.

Key to the success of Clark's system was his rope lock (left) and front-loading arbor (right) sometimes called a carriage or frame. A six foot arbor with a capacity of 675 pounds was sufficient in an era when the heaviest loads were drops, drapes, or canvas flats, with taller arbors provided for permanent borderlights and the light bridge. Linesets were trimmed at the arbor and connected to the batten with a clove hitch and a single cable clip, a method endorsed by the makers of the Crosby clip.

Loft blocks which could slide along the gridloft deck, rather than the overhead stationary wheels of Chicago and the Met, facilitated rapid re-spacing of sets, and mule blocks allowed for curved upstage cyc pipes and side tabs, typical in many Clark installations.

Loft blocks for fire and house curtain at the Broadhurst Theatre (Broadway, 1917) the oldest documented Peter Clark counterweight installation. Clark's name can be seen on the gray wheel.

Probably in about 1920, Clark introduced his trim clamp, a fast way for counterweight flymen to "spike" trim (height) marks for a given stage show.

This 1920 drawing of Broadway's Music Box Theatre illustrates a hemp house being converted to the Clark system in the middle of construction. Clark's revised scheme calls for the planned hemp loading bridges not to be built, and the omitted steel used as the headblock beam for his counterweight system. For a larger view, click here.

Within a dozen years of its inception, Clark's system had become the industry standard, with hundreds of documented installations from coast to coast. To see a list by town of the three hundred twenty-five jobs, click here.

Nor can any claim be found in the obituary for John Clancy.

In stark contrast, the obituaries for Peter Clark tell a different story. The New York Times credited Clark as inventor of "revolutionary stage devices"; the Herald Tribune stated that "Mr. Clark perfected the elaborate system of counterweights [which] banished. . .clumsy backstage sandbags"; the Motion Picture Herald noted that Clark's "development of counterweights vastly simplified the problems of scene shifting;" and Variety wrote that Clark "completely revolutionized stage equipment, notably in his system of stage rigging."

According to "On the Trail of Rigging History" published in the 2010 USITT magazine (and written by the vice-president of marketing for Clancy), "Clancy [in 1912] also unveiled a game-changing innovation: the counterweight system or 'the very wonderful Flowing Weight System designed and installed by Mr. Hagen in the New Theatre [1909]." But by 1912, Claude Hagen was washed up and never heard from again. Below, the New Theatre which was located at Columbus Circle.

Although awe-inspiring in appearance, the New was a white elephant demolished in 1930, and Hagen's waterloo was his Rube Goldberg installation, which substituted noisy lead shot for counterweights.

At least in their annual catalogs, Clancy never "unveiled" Hagen's counterweight system if it ever existed. From a more recent USITT article (written by Rick Boychuk), "The rod arbor first appeared in the 1905 J.R. Clancy catalog." But what Boychuk neglected to mention was that Clancy's weight design was split, not slip, as shown in a 1912 view of the same catalog item.

In fact the slip weight, crucial to the design of Peter Clark's system, was not offered by Clancy until 1926, the same year Clark advertised one hundred and fifteen completed installations.

Theatre authority Wendy Waszut-Barrett unearthed and photographed a counterweight system in Deadwood, South Dakota which utilizes slip weights and possibly served as the inspiration for Clark. But no documentation exists that certifies the maker or the date: it could be 1903, 1923, or 1961. And no remotely similar installation has been found.Perhaps the surviving drawings of Peter Clark, Inc. would give researchers a clue. After Clark's death, his company continued for another eighty years under various names, finally acquired by ETC in 2014 who inherited the drawings, shown here in 1994.

In 2015, ETC shredded every single Peter Clark drawing.

* * *

Peter Clark himself may be found at St. John's Cemetery in Middle Village, Long Island. His funeral was held on West 49th Street at St. Malachy's, the Actor's Chapel, below.

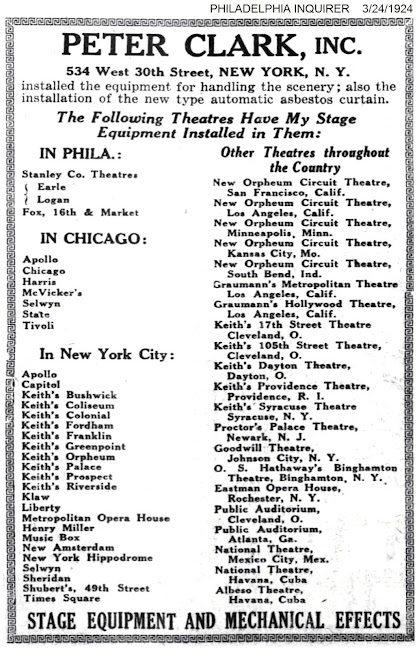

To read more about Peter Clark and his contributions to Radio City Music Hall, click here.A gallery of Peter Clark advertisements follow.

Pictured below is the Keith's Syracuse Theatre (1920).

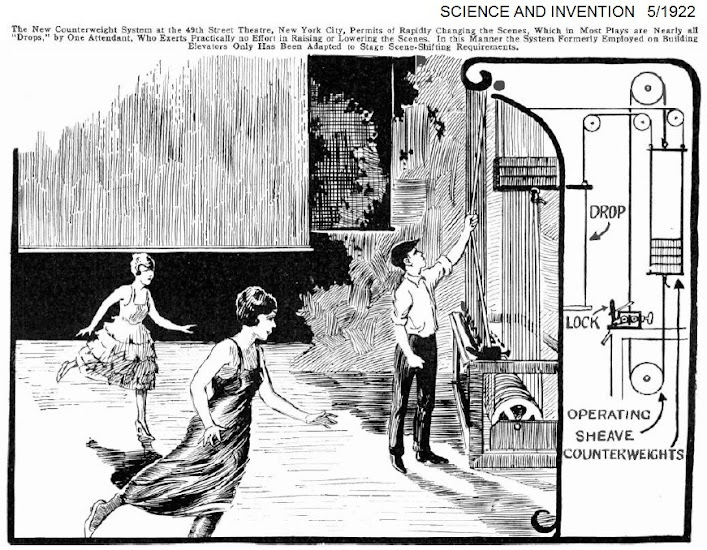

Peter Clark's counterweight system at Broadway's 49th Street Theatre, opened in 1921, is illustrated, but his name is not mentioned. In reality there was a single headblock, not three as shown here.

Pictured is the "Junior Orpheum" Hillstreet Theatre (Los Angeles, 1922)

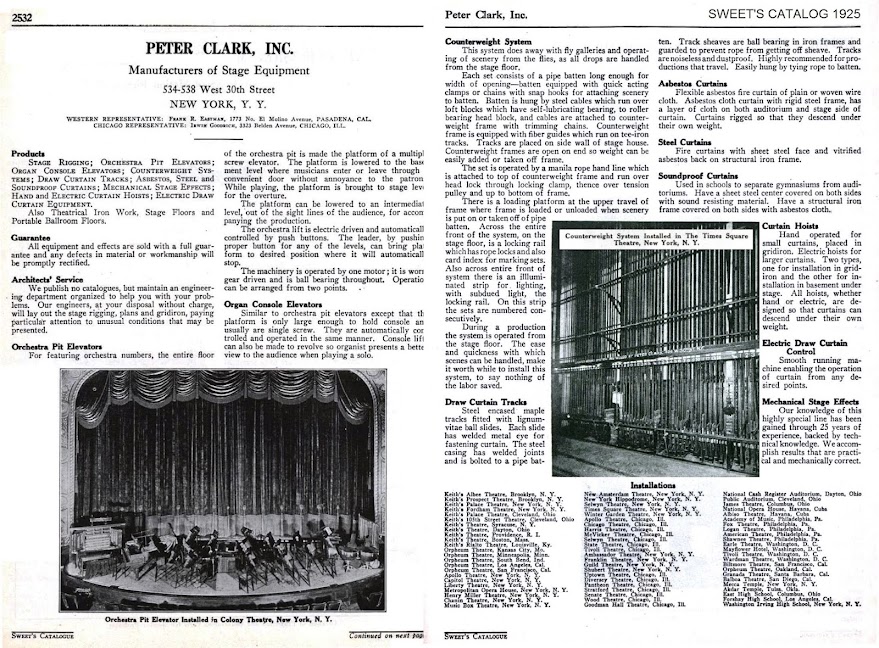

Pictured in the Sweet's Catalog for 1925 are the Colony and the Times Square Theatre (Broadway, 1920). To see a larger view, click here.

In the cut sheet above, Peter Clark announced that they published no catalog, but alternatively offered free engineering drawings. Not until two decades after Clark's death was a catalog published by "successor to Peter Clark" Joseph Vasconcellos. To view that catalog, click here.

The Colony.

Keith's Palace Theatre (Cleveland, 1922).

A listing of 115 Peter Clark counterweight installations as of early 1926. By the time of Clark's death in 1934, the number of documented installations would climb to over 300.

Peter Clark claimed conception, design, manufacture and installation of Paramount Theatre job.

Oriental Theatre (Chicago, 1926).

Peter Clark Inc. expanded from 534-536-538 West 30th Street to include 544-550 West 30th Street.

New York's 1918 Capitol Theatre, hoping to better the Roxy, underwent a major Peter Clark renovation, accomplished in thirty-one days without interruption of service. Unfortunately, no drawing or photos exist of the seven elevators, the new and complete counterweight system, the three wagons, or the automatically controlled overhead bridge

Peter Clark Inc. began operations in 1904, according to this ad, later contradicted.

The Fox Theatre (Washington DC, 1927) better known as Loew's Capitol.

To see a larger view, click here.

In 1928, Clark's operation included a foundry and a staff of eighty-five and the quick-witted Robert Henderson, incorrectly spelled here. Henderson eventually became director of Stage Operations at Radio City. To read the New York Times account, click here.

The Philadelphia Forrest Theatre (1927).

Loew's Syracuse (1928).

The Craig Theatre (NYC, 1928) later known as the Adelphi.

Loew's State (Louisville, 1928) later known as the Palace.

The Philadelphia Scottish Rite Cathedral (1926).

"To permit clearing the stage of horns" for the four-a-day stage shows, horn tracks, lifts, and towers are introduced. Only five Clark Movietone lifts were ever installed, one for each super-deluxe Fox Theatre: Brooklyn, Detroit, St, Louis, San Francisco, and Atlanta.

The 1929 Brooklyn Loew's Kings featured a Clark horn track.

The Fox Theatre (Detroit, 1928), showing the Movietone lift at the "Up" (17'0") position and the lone chorus lift at "Top" (5'0"). Movietone was located directly upstage of the picture sheet.

The Atlanta Fox Theatre Movietone lift at "Down" position and the downstage chorus lift (Atlanta had two) at "Picture" position.

The Enright Theatre (Pittsburgh, 1928).

The Uptown Theatre (Philadelphia, 1929).

The Mastbaum Theatre (Philadelphia, 1929) featured a band car and five lifts.

The Louisville War Memorial (1929).

The Convention Hall (Atlantic City, 1929).

The Warner's Theatre (Atlantic City, 1929).

Fox Theatre (Atlanta, 1929), six elevators.

In this tribute ad to Fox, pictured are two non-Foxes: the Philadelphia Forrest and the Pittsburgh Penn.

The Beacon Theatre (NYC, 1929).

Loew's Pitkin (Brooklyn, 1929)

The Atlanta Fox opened on Christmas Day, 1929, and the Beacon opened the day before.

Clark engineered a six ton glass acoustical curtain for the world's first radio theatre on the New Amsterdam Roof, and three years later, he achieved isolation from the subway vibration for the new NBC Rockefeller Center radio studios by suspending them from the superstructure on cables.

Photos of Clark's installation at the Atlanta Fox Theatre were featured in the May, 1930 Architectural Record.

The New York Daily News Building opened on July 23, 1930 and featured one of Peter Clark's most enduring works.

The Mancall catalog appeared only in 1931. To see a larger view, click here. Pictured is the Atlantic City Convention Hall.

On the occasion of Paramount Pictures' twentieth anniversary.

The Earl Carroll (NYC, 1922) was not originally equipped by Clark, but in the 1931 upgrade he installed a band car, a stage elevator, and motorized rising microphones, later installed in Radio City, after the opening and with RCA 44 mics.

The Southtown (Chicago, 1931).

The Paramount (Boston, 1932).

To see a larger view, click here.

The Times Square Theatre.

Another view of the Uptown Theatre, one of fifteen Balaban & Katz houses entrusted to Peter Clark.

The Met Theatre (Boston, 1925) now known as Wang's.

The Paramount Theatre (NYC, 1926) was the first Clark stage elevator installation ("mechanical stage traps") and band car and the first Clark house with motorized disappearing footlights, necessary for the band car to travel from pit to stage.

From the American Architect, July 1926, the Paramount pit elevators and band car.

The Roxy (NYC, 1927) included seven elevators: three organ consoles, orchestra pit, act (piano) lift, and two contiguous stage lifts.

A glimpse down into the mammoth Roxy orchestra pit, identical in size to the stage, showing two of the three organ console elevators. Roxy (the manager) had unfortunately located all the organ pipes behind the pit grill-work, so unless the pit was at the "Bottom" (storage and loading) position, the chambers were almost completely blocked.

The Missouri Theatre (St. Joseph, Mo., 1927). To see a larger view, click here.

"To be Peter Clark equipped is to be thoroughly equipped for all of time" -- the first announcement of Peter Clark's remarkable lifetime guarantee. The Paramount-Publix Theatre Circuit owned or controlled sixteen hundred Movie Palaces and combined with the other super chains for whom he worked (Fox, Loew, and RKO) Clark had influence over twenty-eight hundred houses altogether.

The Marbro Theatre (Chicago, 1927).

A shot of the Marbro orchestra pit pit, taken from the 1943 IATSE Fiftieth Anniversary program book. Unique to many of Chicago's movie palaces were orchestra conductor (solo) lifts.

A view of the Capitol stage, post-renovation, showing what a few elevators can do.

This ad pictures the Colony but headlines Atlanta's Georgia Theatre, later known at the Roxy.

Renovation of the Stanley, Pittsburgh (1922).

Paramount-Publix.

The Warner's Hollywood (NYC, 1930), later known as the Mark Hellinger.

In May, 1930, Clark installed at the St. Louis Muny Opera the forty-nine foot diameter "largest turntable in the world," six feet wider than the 1932 Radio City revolve.

Clark's motorized screen adjuster closed in (or opened up) the sheet masking by simultaneously moving a border and a set of legs to any of three preset positions, controlled remotely from the stage and the projection room.

Arthur E. Clark, listed below as the ad man, was apparently the only one of Peter Clark's five sons who followed in his tracks, becoming general manager after the death of his dad.

Included in the above ad as a recent installation is the Ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria (New York, 1931), possibly the only ballroom with a fly system and three stage elevators. Drawn with a Leroy Lettering Set. For a larger view, click here.

Loew, Paramount, Fox, Orpheum, Warner's, and Stanley are mentioned as clients.

The only article authored by Peter Clark appeared in the Architectural Forum of September, 1932. To view the article, click here. Photographs included shots of the elevators within elevators at the Philadelphia Convention Hall (1931).

Radio City Music Hall (NYC, 1932).

Mention is made of "Clark's Catalog No. 232," but no Clark catalog of any description has yet been unearthed.

RKO Roxy (NYC, 1932) later known as the Center Theatre.

The final advertisement in Peter Clark's lifetime.

The Trade obituary for Peter Clark.

To view the obituaries in the New York Times, the New York Herald Tribune, and the New York World-Telegram (includes editorial), click here.

Peter Clark was a friend to all.

On the occasion of the fifth anniversary of Radio City Music Hall.

November 8, 2021

Bob Foreman spent his career restoring old theatres and is a long-time member of IATSE and an ESTA-certified theatre rigger.

For a master index of all of Bob Foreman's photo-essays, click here.

Acknowledgements

In alphabetical order, Giovanni Angotti, Winston Atkins, Joe Booth, Rick Boychuk, Tim Burns, John Calhoun (NYPL--Billy Rose), John Cardoni, Cinema Treasures, the Peter Clark family, Peter Clark (Met Opera Archivist), Bill Counter, Don Feely, Scott Hardin, Don Hoffend, Jr., Mike Hume, Carlos Martinez, Duncan Mackenzie, John McCall, Joe Mobilia, Garry Motter, Wendy Waszut-Barrett, Michael Zande, and Rick Zimmerman.