This article is about the stage machinery at Radio City Music Hall (1932) and its inventor, Peter Clark. A companion article, describing the Music Hall electrics in detail, can be viewed by clicking here.

Upon his unexpected death in 1934, the show business bible Variety wrote that Peter Clark "had completely revolutionized stage equipment." The Peter Clark counterweight system (right) installed in hundreds of theatres "banished the clumsy backstage sandbags," said the New York Herald Tribune.

"Peter Clark left a greater impression on the modern stage than perhaps any other designer of his time," wrote the New York Times, in his obit which can be read here. Headlines credited Peter Clark as inventor of the orchestra elevator, the hydraulic stage lift, and the stage at the two-year-old Radio City Music Hall, which was hailed as his masterpiece.

Peter Clark was that rare bird whose masterly work included not only permanent installs, but also the transitory, inventing the mechanisms behind increasingly elaborate New York stage productions. His shop built the stage devices and entire complex settings that graced the stage productions at the Metropolitan Opera (for which he was also their engineer of record), and for the Broadway spectacles of George White, Earl Carroll, Sam Harris, and Zeigfeld, for whom he worked beginning in 1907. Peter Clark was always a generous man, and the proceeds from his first ad (1910) went to benefit actors.

To set the record straight, Peter Clark invented neither the orchestra nor stage elevator, but he standardized their design, construction, and installation, with two hundred lifts in one hundred theatres to his credit. In 1884 when Clark was only six years old, the modern stage lift was introduced in Europe by the Asphaleia Syndicate, purveyors of badly needed fireproof stages. First patented in Germany and fabricated in Vienna, the fanciful array of direct-acting hydraulic lifts (non-working model, left) were intended to satisfy the increasingly complex scenic demands of operas such as those by Richard Wagner, shown with dragon Fafner (right). Only three Asphaleian houses were built: Budapast (1884), Halle an der Saale (1886) and Chicago's Auditorium Theatre (1889). To view the US patent, click here.

To see all of Peter Clark's advertisements and a detailed view of his counterweight system, click here. The emergence of studio-owned Movie Palaces proved a goldmine for Clark's shop, and Peter Clark equipped two-hundred and fifty of the largest, all of them with fully equipped stages necessary to facilitate the live shows which split the bill with silent films, many houses with staff orchestras and dancers. Movie Palaces were nonexistent when blockbuster "The Birth of a Nation" premiered in 1915, and its first class roadshow toured with a thirty piece orchestra which could only fit into available legitimate theatres (below). So staggering were the "Nation" box office receipts that the studios rushed to build their own theatres and keep the profits for themselves.

1927 was the peak building year (below) when an astounding one thousand theatres sprang up like Topsy. By late 1930, almost eleven thousand temples to the Motion Picture had been wired for sound.

Peter Clark became the go-to guy for the studio chains, and his documented counterweight installs include twenty houses each for Paramount and Loew (MGM); a dozen for Fox; ten for RKO (including Radio City Music Hall); and seven for Warner's. For the independents, he boasted fifteen installs for Chicago's Balaban & Katz, and three for Grauman of Los Angeles. Theatres below are Loew's Jersey [City], the Amarillo Paramount, the Atlanta Fox, the Chicago Chicago, New York's RKO Roxy a/k/a Center Theatre, and Erie's Warner.

The New York Roxy Theatre (below left) also opened in 1927 and marked the ascension of impresario "Roxy" Rothafel from producer to saint, his latest parish chapel known simply as "The Cathedral of the Motion Picture." Located adjacent to the Hotel Taft at 7th Avenue and 51st Street, the grandeur of the largest theatre in the world (6200 seats advertised) continued to boggle minds two years later, when The New Yorker's Helen Hokinson asked, "Mama, does God live here?"

The Roxy was also one of the first theatres to be equipped for sound, with talking picture apparatus installed as original equipment, its Western Electric 16-A shallow sound horns mounted on the rear of the picture sheet (left). Talkies proved a boon for Clark, especially "the new type of screen frame" (right), remotely operated, which automatically modified the sheet masking to fit silent, sound, or widescreen. He installed over two hundred of these assemblies, named "Magnascope" after the Paramount wide-screen process.

Clark branched out into lift-building starting in 1924 (below, left) and by the opening of the Roxy (center), he had forty elevator installs under his belt. A Peter Clark lift was an electrically-driven worm-gear machine, utilizing a deep-thread screw (right) which in the case of brake failure, would slowly drift downwards-- not crash. (To see a list of the two-hundred and sixteen documented Clark elevator installations by town, click here.)

Talkies had replaced silents by late 1929, but elaborate stages continued to be built, because many in the studios believed sound to be a passing fancy. Following on the heels of the Roxy opening, a new kingdom of Super-Deluxe Movie Palaces began to proliferate, and the Atlanta Fox (1929) exemplifies a fully-loaded Clark install, with six elevators. Remote push button stations allowed the organist and conductor to control their respective lifts. Left the stage manager's panel and right, the elevators.

A view facing downstage left of the trap room at the San Francisco Fox shows the telescoping guide rails which were required to stabilize these free-standing elevators, when they rose above the stage. All the lifts were supplied with black velour masking on the upstage and downstage sides.

Movietone lifts, located directly upstage of the Picture Sheet, contained three Western Electric (ERPI) sound horns and played at seventeen feet above the stage. Movietone was the fastest of the Clark lifts, able to reach DOWN (flush with the stage) in fifty seconds to clear the deck for the stage show-- four times a day. Below, the Atlanta Fox Movietone lift, still in service today, shown at UP position (left) and DOWN (right).

Four of the twenty-one screws at the Atlanta Fox can be seen below left, looking upwards at the two stage lifts. On the right is a view of the Reliance drive motor for the orchestra pit and Clark's spherical limit switch. If a lift ran past a permanent limit, two of the three power legs to the controller would be interrupted, stopping everything.

Below is the simple controller for a lift with an intermediate PICTURE stop. Pressing PICTURE would send a given lift to its elevation during a film: Stage lifts flush with deck and the Orchestra Pit just low enough so that patrons could see over the harp.

View of stage motor room, facing downstage.

Three weeks after the date of the Core Drilling Specification, boring for the orchestra and stage elevators was underway. The first public description of the Music Hall stage mentions the centerpiece of the stage design, the traveling Band Car.

Popular Mechanics illustrated the drilling, headlining the Band Car as "an orchestra on elevators and track."

Rumors persist that Otis Elevator built the Clark lifts, but documentation does not support that theory. In July 1931, Roxy and Nelson Rockefeller witnessed a demonstration of worm-gear stage lifts at the Otis Works in Yonkers, but the contract went to Peter Clark. (The Music Hall passenger lifts are Otis.) Two years after Clark's death, it was printed that the Philadelphia branch of the Baldwin Locomotive Works "constructed these elevators" but once again, no device on the stage is branded anything other than "Peter Clark, Inc." It is obvious, however, that seventy-foot long I-beams and forty-eight foot long pistons were too lengthy to be fabricated in the Clark shop.

Clark's working model was installed in the Art & Costumes office, and until costs became prohibitive, a scaled setting was built for every new production.

A view of the orchestra seating steel framing in progress, the holes for the orchestra pit and stage elevators seen beyond. Billed as having 6200 seats, the drawings say 5945, a net gain of twenty-five seats over the Roxy-- formerly the World's Largest Theatre.

Not until the building was half-finished was Peter Clark awarded the contract for the Music Hall and its sister theatre on 49th Street, the RKO Roxy (Center Theatre.)

"Everything in this house is on a tremendous scale," wrote The New Yorker after their sneak preview visit, "and the orchestra pit is as large as the ordinary stage." Thirty-six Rockettes (below) can hardly been seen, as rendered by artist Harvey Schmidt, who also composed The Fantasticks.

The job name was "Theatre No. 10" of Metropolitan Square, the working title for Rockefeller Center. Architects credited were Reinhard & Hofmeister; Corbett, Harrison & MacMurray; and Hood & Fouilhoux. Except for Clark's work, the Consulting Engineer was Clyde R. Place. This drawing is marked "Building Department Revisions, January 8, 1932."

An idea of the complexity of the mechanical plant can be seen here. "U-re-lite" refers to a circuit breaker, a relatively new invention.

And indeed, five hundred would be needed to fill a stage with a hundred-foot opening. An architect's rendering (left) hopes that seven players will be sufficient, but the entire Corps de Ballet of fifty-eight (right) was nearer the mark.

Two stage entrances and two dressing room towers flank the stagehouse, two elevators per side and dressing rooms to accommodate six hundred. In this view can be seen the bronze Scene Door (left) and the 51st Street Stage Entrance to its right. The stage was one floor down from Street Level.

A plan of the orchestra level, showing the relation to the parent company RKO's office building.

A plan of the Stage Level wings. The principal actor crossover (not shown here) was provided upstage of the Cyc Foot traps. There were at least three Lamp Rooms in the theatre, housing replacements for the 25,000 light bulbs used the Music Hall.

A view of the 2nd Floor, one level up from Street.

The seventh floor of the 50th Street Dressing Room Tower (right, bottom) contained the dormitory and infirmary for the dancers, all female, who hardly ever left the building. The Roof Garden was packed with earth thirty inches deep and featured thirty-foot high trees. Below the roof was the Studio Level (8th Floor) which was not accessible from the Backstage Elevators, but served by the small Executive elevator car (left), which led directly into Roxy's apartment. There was also a lower intermediate level, front and back, containing the projection rooms and tryout rooms, respectively.

The Studio Level was almost at the same elevation as the grid (left). The mezzanines shown center top contained a very private Studio with bath, possibly for use as Roxy's guest room (left); and the other contained the sleeping quarters for Roxy's pad, two bedrooms ("Studios"); two baths; three walk-in closets; and two dressing rooms.

A view of Roxy's suite facing the stagehouse, with ceilings almost twenty-five feet high. To give an idea of scale, the Rehearsal Hall (above) is four times larger than the room shown below.

The Music Hall was so Deluxe that it had three identical vertical signs, all shown below. Most theatre manager's offices were windowless; Roxy's had three in a corner office overlooking the Sixth Avenue marquee, directly behind the vertical sign in the foreground.

It was an unfortunate fact that accurate directions to the Music Hall Executive Offices (green arrow) were "Go in the men's room and take a sharp right." Below shows the relationship between the Executive Car (left) and the office suite. The elevator was accessible from a street entrance, one floor down.

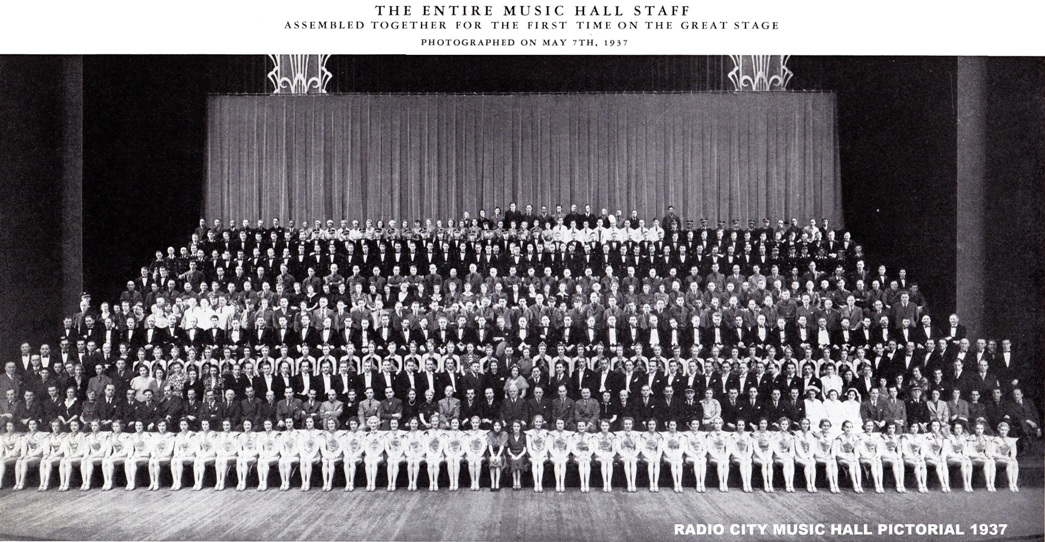

Five years after opening the staff was photographed and numbered five hundred and fifty-six.

They could mix and mingle during the films in the basement cafeteria (top center) located along the long corridor from backstage to front of house.

Because the grid was only forty-five feet higher than the sixty-foot-high proscenium arch, the forty-eight ton fire curtain was constructed in two overlapping steel-framed sections, the upper and lower sections shown in the photo below. "It comes in with a roar...[almost free-falls] and at about twelve feet above the deck, hydraulic plungers slow it," wrote former Chief Projectionist Robert Endres in Cinema Treasures about a "fire drop test."

The Contour Curtain, immediately upstage of the Fire Curtain, was the first of its kind, and Clark shared the patent with inventor Ted Weidhaas (by his father Gustav), and Howard Harding. (To view the patent, click here.) In this schematic, the top row shows the adjustable up and down limit sliders on the Control Panel and the bottom rows shows the thirteen motor controllers.

A back-lit chart on the twelfth row rehearsal table showed the stage lighting positions and their corresponding Rehearsal Letters, starting with A for footlights. Stage director at the Music Hall for forty-two years (and Roxy's successor) Leon Leonidoff is pictured at the table which included a "god mic," invented for Roxy by Western Electric in 1923. Leonidoff, who conceived the Christmas and Easter shows among hundreds, used an ashtray, and the Music Hall had twenty-eight hundred of them, along with fifty-five Watchman's Clocks, eighty-one exits, seven hundred and six mirrors, and thirty-five hundred keys.

A special counterweighted set was provided to facilitate maintenance of the Contour Curtain, which was made up of sections.

This doctored photo illustrates the "Inner Proscenium" a motorized portal that could mask the stage down to the size of a doorway, according to the spec. The border was on a special motorized lineset, and the legs were on sixty-foot-high vertical rolls which tracked at the top. The portal has been long removed, and its lineset location is unknown. It could have been set immediately downstage of the Fire Curtain, as the fire department had allowed a full height traveler downstage of the asbestos at the Music Hall's sister theatre, the Center. The conjectural placement shown below would allow the Contour Curtain to be masked out.

From 1932 until 1979, the Music Hall operated as a Super Deluxe presentation house, premiering a first run picture and a fifty-minute stage spectacle, with a top price of $2.75 to the very end. Four-a-day on weekdays and five on weekends combined to make a thirty-performance-week for the resident orchestra, male glee club, the Rockettes, and the Corps de Ballet, the latter group shown below in "The Undersea Ballet," arguably Leonidoff's best spectacle ever, a permanent fixture in his forty years of rotating repertoire. A new stage show was produced every two to four weeks, depending on the run of the picture.

The mechanics of the Music Hall stage were the dream of every schoolboy, who had to make do with slow and labor-intensive set changes on their high school stages.

For at the Music Hall there was a magical Control Panel where one man with a well-aimed finger could do the work of fifty. The panel controlled the thirteen separate devices necessary to play a show and to make the changeover from stage show to picture, and not a single more.

The Control Panel was a one-of-a-kind, and likewise so were its operators, Earl Marshall shown here, the first of four in the history of the Music Hall.

George Ballant, the second operator, circa 1956. The Control Panel will be further examined after a look at the stage.

There were seventeen motorized sets, with rigging on the opposite wall, including four light bridges named "Borders E-F-G & H" in Music Hall parlance, to correspond to the Rehearsal Letters. F and E (light bridges) and D are seen in this view, facing the fire curtain. Because the motorized E Border contained supplementary horns for the movies, it was operated from the Control Panel. Borders F, G,H, the Cyc and all other motorized sets (except as described below) were operated from a control box, set within the center of the pinrail.

Originally the primary sound horns were suspended from a motorized trolley beam, but with the conversion to CinemaScope, the new cabinets were mounted to the back of the Picture Sheet and on E Border. Vertical and horizontal functions for the I-beam trolley, which could clear in fifty-five seconds, were activated from the Control Panel.

A matte shot from the 1942 Hitchcock film "Saboteur" paints a realistic picture of how small picture sheets were before CinemaScope, and the Music Hall was no exception. To the left and right of the stage can be seem the motorized picture sheet traveler known as "the Golds," which got a lot more use than the Contour, which was generally used only at the top and bottom of a show. The Control Panel allowed the Golds four speeds in either direction, slow for the feature and fast for the shorts. Smoking was allowed backstage during shows, but only if the Picture Traveler was closed.

The frame for the CinemaScope picture sheet measured forty-seven by one hundred and seven feet wide and was installed in 1953. Because the Music Hall was the only film theatre still presenting live shows at that time, the frame was made flat, not curved, or otherwise it would occupy too much fly space. The sheet was on a motorized lineset controlled from the Panel, as were the Clark Magnascope controls. The guide cables for the sheet were five inches downstage of Elevator 1, and red warning lights mounted to the underside of this huge Picture Sheet/Horn assembly flashed rapidly when the sheet was in motion.

Between forty and sixty stagehands were required to put up these spectacles, many of them manning the thirty-six follow spots, twelve in the booth alone, with others located in auditorium D Cove, the inner proscenium, stage side bridges and wing light towers. The stage of the Music Hall with its four elevators, turntable, and Band Car has been the subject of many feature stories which are listed in the bibliography.

For the Band Car to work, the multiple Music Hall organ consoles were shunted to a less flamboyant position, placed on motorized cars behind the drapes, circled below. The Band Car also precluded an act lift, a Movietone lift, and lift controls on the conductor stand, standard equipment with Clark's worm-gear jobs.

Generally, the Band Car lived on the pit elevator (left below) and connected electrically via floor pockets on the stage right (control) side. The orchestra pit elevator had four preset stops, numbered "1" to "4" and operated from the Control Panel. The pit, as with the stage lifts, featured automatic deceleration, but the operator could stop the lift at any position and run at any rate of speed. When the lift reached BOTTOM, a Switch Man in the garage would kill power to the elevator at any time that the Band Car was in motion. Similar lockout switches were provided for the stage lifts. To see a larger view, click here.

Shown at TOP position below, the orchestra pit lift was six inches wider than the stage elevators, and without the Band Car, weighed forty tons. Mechanical retractable pins on the downstage edge of the pit lift prevented the Band Car from rolling into the house, but retracted when the lift was at BOTTOM.

Below the lift is shown at OVERTURE position, so that the Band Car sits flush with the deck. The advantage of not having a preset button for this level allowed the operator to achieve dramatic impact by shooting the lift upwards from the PRESET position to TOP at a high rate at of speed, then rapidly decelerating right before hitting the target, for a fast and hard stop. Dramatic impact was standard practice at the Music Hall, where four men were required to operate the giant-sized travelers-- two men on the ropes, and two on the leading edges of the drape to ensure a graceful closure.

The New Yorker-- which was never wrong-- credited the Band Car invention to Peter Clark.

But Peter Clark did not invent the Band Car-- it was the brainchild of Jack Partington, a west coast stage director/inventor. Partington also conceived the idea of the "migrating bandwagon" to jazz up his stage shows, which included an on-stage jazz band. A handful of his "Magic Flying Stages " were installed, including in Chicago's Oriental Theatre, where the stage lifts were Partington hydraulic and the pit lifts were Peter Clark worm-gear-- installed at the same time. Jack's greatest contribution was almost immediately adopted by every theatre in the nation: the concept of a "Presentation House" where overtures and preludes were supplanted by fast onstage antics to showcase the picture.

The only solid portion of the Music Hall stage was twelve feet, ten and one-half inches deep and referred to as "the wood." Besides the pit, the Band Car could fit onto Elevators 1 and 3, but not on the center elevator or the Wood. When the elevator system was turned on for a day's work, Clark's inching device was activated, automatically holding a given lift flush with the stage, or at any other chosen height-- within one/sixteenth of an inch. As Modern Machine Shop noted in a 1937 article, "the stage breathes."

The electrically-driven travelling Band Car was intended for seventy-five musicians and was the size of a horizontal locomotive (it ran on two tracks), weighing in at twelve and a half tons, including passengers. A driver, known as the Band Car Driver, manipulated the Upstage/Downstage/Stop motor control from his prone position within the upstage right corner of the Car. The Band Car Driver could see upstage, but not downstage, so a spring-loaded limit switch wheel was mounted on the downstage side which would stop the Car if it the wheel fell below deck elevation, as in the case of an elevator hole.

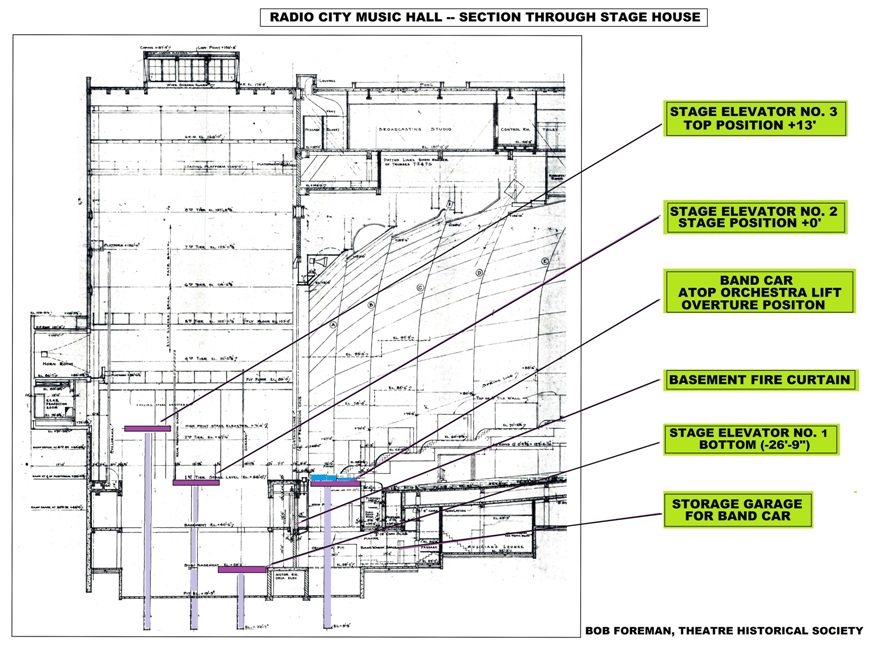

A section view of the stage showing the elevators and also showing the Studio and intermediate level rooms (top right). For a larger view, click here.

Thinking "three-dimensional chess game" might help your understanding of this chart. Start at top right.

The Band Car is shown atop Elevator No. 3 in this fact-filled illustration.

A clever invention allowed Partington's dream to be realized so the orchestra could be heard even from the subbasement. A special traveling cable was made up whereby the output from the newly-invented RCA microphones (left) used on the pit could be paralleled, as shown on the right, and the audio signal never interrupted. Connections were made and unmade by the Band Car Driver and two cable wranglers, concealed by the Band Car back masking. For a larger view of the diagram, click here.

The Music Hall stage was equipped with "54 microphone positions on or above the stage" as shown below. Also shown in yellow are the approximate positions of the traps for the five "disappearing" mics which would rise five foot when activated from the audio booth in the projection room. Installed after the Hall opened, the devices were likely the work of Peter Clark who had invented and installed microphone lifts in the Earl Carroll in 1931.

The "wood" was wood, and the rest of the stage, battleship linoleum surrounded by gleaming glazed brick. The motorized disappearing footlights could vanish in about twenty-five seconds to make way for the Band Car. When activated, the Steam Curtain shot up a spray of 212 degree Con Ed vapor to make a sort of scrim, the condensation (hopefully) captured in the excelsior-lined trough.

Power to the Band Car motor and music stand lights was originally provided by sixty internal Exide Ironclad batteries (which themselves weighed one and a half tons), but was soon converted to motor-generator-produced 130 volts DC, fed by traveling cable. Because DC cannot be paralleled, the pit lights could be seen to blink when the changeover was made. A typical changeover (DC and audio) took fifteen seconds.

A view of the Band Car Driver during a maintenance session.

Dance numbers were choreographed always placing the Rockettes at least six feet from any vast, open hole.

A 1949 advertisement for Socony Oil showcased the elevators, which were driven not by hydraulic fluid, but by a mixture of water and (Socony) cutting oil, along with an anti-bacterial treatment. Elevator 2 was "the brains of the operation" containing the turntable motor and the electric solenoids which pin ("clutch") the three lifts together to make a turntable.

A view of the pit elevator pit, showing on the left "the island" (which corresponded to the "wood" two floors above) and the Band Car garage to the right. Splitting the island horizontally is the subbasement fire curtain which fills the rectangular opening shown. Beneath the pit lift was a counter-weighted safety railing would sink out of view when the elevator lit upon it. It was stipulated by contract that the orchestra start and finish a performance at this subbasement level, adjacent to their locker and club rooms, but not accessible from the backstage elevators. which terminate on the Shop (basement) level, one long flight above.

A view of the subbasement fire curtain which continues the proscenium fire wall and prevents a stage fire from reaching the house.

While the Budapest and Halle houses featured a hydraulic fly system, the Chicago Auditorium was wisely equipped with the first counterweight fly system in the United States, an invention credited to Fritz Brandt, the Mechanical Director at Wagner's Bayreuth opera house. Brandt also invented the orchestra pit elevator, unveiled in Wiesbaden (Prussia) on October 16, 1894, which remained one-of-a-kind until the first pit lift was installed on Broadway in 1922.

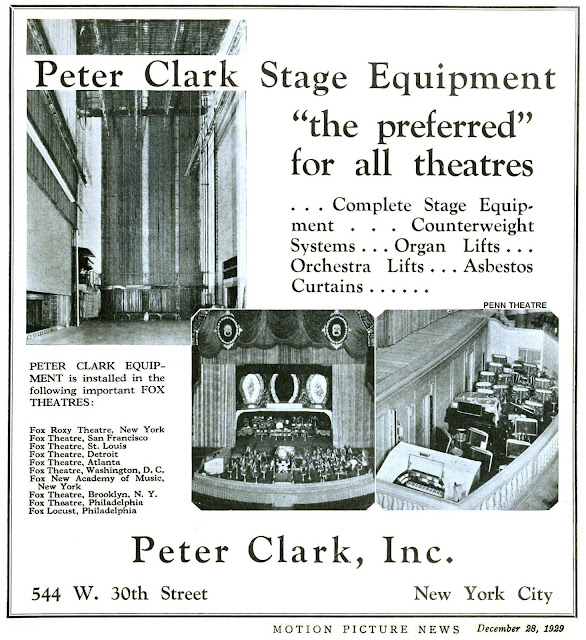

Counterweight rigging did not begin to proliferate until twenty years later when Peter Clark perfected his system, which sounded the death knell for "hemp houses." The Peter Clark system was both labor-saving and fireproof, with steel cable instead of flammable rope pickups; iron stage weights for sandbags; and a stage level locking rail, which eliminated multiple fly galleries. Clark introduced his counterweight system about 1913, and a dozen years later his installations had become the industry standard, with three hundred installations from coast to coast, as evidenced by this 1929 advertisement. (To see a list of the three hundred and forty-five documented Clark installations by town, click here.)

Peter Clark was a man at the right place at the right time. Riding the frenzied crest of New York legitimate theatre construction, Clark's shop equipped almost fifty Broadway playhouses with his new counterweight system, including most of the houses currently owned by the Shuberts, green circles below.

1927 was the peak building year (below) when an astounding one thousand theatres sprang up like Topsy. By late 1930, almost eleven thousand temples to the Motion Picture had been wired for sound.

Peter Clark became the go-to guy for the studio chains, and his documented counterweight installs include twenty houses each for Paramount and Loew (MGM); a dozen for Fox; ten for RKO (including Radio City Music Hall); and seven for Warner's. For the independents, he boasted fifteen installs for Chicago's Balaban & Katz, and three for Grauman of Los Angeles. Theatres below are Loew's Jersey [City], the Amarillo Paramount, the Atlanta Fox, the Chicago Chicago, New York's RKO Roxy a/k/a Center Theatre, and Erie's Warner.

The New York Roxy Theatre (below left) also opened in 1927 and marked the ascension of impresario "Roxy" Rothafel from producer to saint, his latest parish chapel known simply as "The Cathedral of the Motion Picture." Located adjacent to the Hotel Taft at 7th Avenue and 51st Street, the grandeur of the largest theatre in the world (6200 seats advertised) continued to boggle minds two years later, when The New Yorker's Helen Hokinson asked, "Mama, does God live here?"

Clark branched out into lift-building starting in 1924 (below, left) and by the opening of the Roxy (center), he had forty elevator installs under his belt. A Peter Clark lift was an electrically-driven worm-gear machine, utilizing a deep-thread screw (right) which in the case of brake failure, would slowly drift downwards-- not crash. (To see a list of the two-hundred and sixteen documented Clark elevator installations by town, click here.)

Talkies had replaced silents by late 1929, but elaborate stages continued to be built, because many in the studios believed sound to be a passing fancy. Following on the heels of the Roxy opening, a new kingdom of Super-Deluxe Movie Palaces began to proliferate, and the Atlanta Fox (1929) exemplifies a fully-loaded Clark install, with six elevators. Remote push button stations allowed the organist and conductor to control their respective lifts. Left the stage manager's panel and right, the elevators.

Movietone lifts, located directly upstage of the Picture Sheet, contained three Western Electric (ERPI) sound horns and played at seventeen feet above the stage. Movietone was the fastest of the Clark lifts, able to reach DOWN (flush with the stage) in fifty seconds to clear the deck for the stage show-- four times a day. Below, the Atlanta Fox Movietone lift, still in service today, shown at UP position (left) and DOWN (right).

Four of the twenty-one screws at the Atlanta Fox can be seen below left, looking upwards at the two stage lifts. On the right is a view of the Reliance drive motor for the orchestra pit and Clark's spherical limit switch. If a lift ran past a permanent limit, two of the three power legs to the controller would be interrupted, stopping everything.

View of stage motor room, facing downstage.

The Atlanta Fox had opened three months after the stock market crashed in October, 1929, and it was the last Super-deluxe Palace to be built. From a peak of eighty-five employees and forty jobs in 1927, Peter Clark's work fell to half that number in both 1930 and 1931, and down to six in 1932. For Clark and his boys, the construction of Radio City was the final frontier, the chance to earn all the money they'd need for the rest of their lives. And no expense would be spared on the most expensive theatre ever built.

Roxy was hired away from the Roxy Theatre and began working for the Rockefellers in April, 1931. But according to Charles Francisco's 1979 book about the Music Hall, Peter Clark was in on the design of the theatre from the conceptual stage, meeting with Roxy and his stage director Leon Leonidoff beginning in early 1930, while the latter pair were still employed by the Roxy. That Peter Clark was considered one of the designers of the Music Hall is verified by this excerpt from June, 1931.

Roxy was hired away from the Roxy Theatre and began working for the Rockefellers in April, 1931. But according to Charles Francisco's 1979 book about the Music Hall, Peter Clark was in on the design of the theatre from the conceptual stage, meeting with Roxy and his stage director Leon Leonidoff beginning in early 1930, while the latter pair were still employed by the Roxy. That Peter Clark was considered one of the designers of the Music Hall is verified by this excerpt from June, 1931.

Simultaneously, the Rockefellers were building two theatres for Roxy to manage: the Music Hall (below, left) and the RKO Roxy (right) located two blocks south. For technical details of the RKO, soon to become the Center Theatre and demolished in 1954, click here.

In September 1931, Peter Clark's beaming face first appeared in the press when he sailed off to Europe with Roxy and a group which included architects Harrison and Reinhard, and four representatives of the National Broadcasting Company. NBC was in search of technical data for their 30 Rock studios (which opened in November, 1934), which Clark also helped design.

On the boat ride home, Roxy and Clark met Francis Mangan, a man who insisted that Peter Clark equip his yet unbuilt cinema in Paris with "the same stage machinery" as the yet unbuilt Music Hall. The 3500-seat Paris Rex (still in operation) was designed by John Eberson and also opened in December, 1932. The construction shot (left) seems to indicate that only a single stage lift could fit their shallow stage.

Peter Clark's name appears not at all in the massive Radio City Music Hall stage specification, and only once as a footnote in the specification for the stage elevator core drilling. Nor is any other engineer named. Thus it is a fairly good assumption that Clark wrote his own ticket, working both as designer and consulting engineer before the building went up. To see both specs, indexed, click here.

In September 1931, Peter Clark's beaming face first appeared in the press when he sailed off to Europe with Roxy and a group which included architects Harrison and Reinhard, and four representatives of the National Broadcasting Company. NBC was in search of technical data for their 30 Rock studios (which opened in November, 1934), which Clark also helped design.

On the boat ride home, Roxy and Clark met Francis Mangan, a man who insisted that Peter Clark equip his yet unbuilt cinema in Paris with "the same stage machinery" as the yet unbuilt Music Hall. The 3500-seat Paris Rex (still in operation) was designed by John Eberson and also opened in December, 1932. The construction shot (left) seems to indicate that only a single stage lift could fit their shallow stage.

Three weeks after the date of the Core Drilling Specification, boring for the orchestra and stage elevators was underway. The first public description of the Music Hall stage mentions the centerpiece of the stage design, the traveling Band Car.

Popular Mechanics illustrated the drilling, headlining the Band Car as "an orchestra on elevators and track."

The use of hydraulics instead of worm-gear at the Music Hall marked an abrupt departure for Clark, an entry into an entirely new field. But he had on his staff Howard V. Harding, a man with a nautical design background, who served as his Chief Engineer for a decade. Four years after Clark's death, Harding announced publicly that he "designed the the hydraulic stage lifts in Radio City Music Hall," but "Peter Clark" is the sole name on the patent (below) filed in March, 1932. The patent included the turntable-within-the lifts, the lift equalizer mechanism, and the plumbing; excluded was the Band Car, the electric selector system, and the Control Panel. To see the patent, click here.

Clark's hydraulic lifts would prove to be his crowning achievement, and such was their perfection that a year after his death, his firm was hired to adapt the Music Hall elevators for use on Navy aircraft carriers.

Peter Clark guaranteed his work not for one year or five, but "for all time" via his "perfected organization."

Peter Clark is shown demonstrating his 1/2" scale model of the Music Hall stage, which included prototypes of his electrical inventions which controlled the elevators, turntable, and Band Car, all fully functional. The model was pneumatic, not hydraulic, so as with the successful realization of the untested Ferris wheel thirty years before, Peter Clark trusted to hope on a gigantic scale.

Clark's working model was installed in the Art & Costumes office, and until costs became prohibitive, a scaled setting was built for every new production.

A simulated glimpse of the theatre interior was unveiled in the March 1932 Architectural Record, showing models large enough to live in. No balcony, but three mezzanines, irreverently referred to as "shelves."

A view of the orchestra seating steel framing in progress, the holes for the orchestra pit and stage elevators seen beyond. Billed as having 6200 seats, the drawings say 5945, a net gain of twenty-five seats over the Roxy-- formerly the World's Largest Theatre.

Not until the building was half-finished was Peter Clark awarded the contract for the Music Hall and its sister theatre on 49th Street, the RKO Roxy (Center Theatre.)

In August the firm claimed design credit for the Music Hall stage (below green) in addition to execution and installation.

"Everything in this house is on a tremendous scale," wrote The New Yorker after their sneak preview visit, "and the orchestra pit is as large as the ordinary stage." Thirty-six Rockettes (below) can hardly been seen, as rendered by artist Harvey Schmidt, who also composed The Fantasticks.

The job name was "Theatre No. 10" of Metropolitan Square, the working title for Rockefeller Center. Architects credited were Reinhard & Hofmeister; Corbett, Harrison & MacMurray; and Hood & Fouilhoux. Except for Clark's work, the Consulting Engineer was Clyde R. Place. This drawing is marked "Building Department Revisions, January 8, 1932."

A cast of five hundred performers opened the house.

And indeed, five hundred would be needed to fill a stage with a hundred-foot opening. An architect's rendering (left) hopes that seven players will be sufficient, but the entire Corps de Ballet of fifty-eight (right) was nearer the mark.

Two stage entrances and two dressing room towers flank the stagehouse, two elevators per side and dressing rooms to accommodate six hundred. In this view can be seen the bronze Scene Door (left) and the 51st Street Stage Entrance to its right. The stage was one floor down from Street Level.

A plan of the orchestra level, showing the relation to the parent company RKO's office building.

A plan of the Stage Level wings. The principal actor crossover (not shown here) was provided upstage of the Cyc Foot traps. There were at least three Lamp Rooms in the theatre, housing replacements for the 25,000 light bulbs used the Music Hall.

A view of the 2nd Floor, one level up from Street.

The seventh floor of the 50th Street Dressing Room Tower (right, bottom) contained the dormitory and infirmary for the dancers, all female, who hardly ever left the building. The Roof Garden was packed with earth thirty inches deep and featured thirty-foot high trees. Below the roof was the Studio Level (8th Floor) which was not accessible from the Backstage Elevators, but served by the small Executive elevator car (left), which led directly into Roxy's apartment. There was also a lower intermediate level, front and back, containing the projection rooms and tryout rooms, respectively.

The Studio Level was almost at the same elevation as the grid (left). The mezzanines shown center top contained a very private Studio with bath, possibly for use as Roxy's guest room (left); and the other contained the sleeping quarters for Roxy's pad, two bedrooms ("Studios"); two baths; three walk-in closets; and two dressing rooms.

A view of Roxy's suite facing the stagehouse, with ceilings almost twenty-five feet high. To give an idea of scale, the Rehearsal Hall (above) is four times larger than the room shown below.

The Music Hall was so Deluxe that it had three identical vertical signs, all shown below. Most theatre manager's offices were windowless; Roxy's had three in a corner office overlooking the Sixth Avenue marquee, directly behind the vertical sign in the foreground.

It was an unfortunate fact that accurate directions to the Music Hall Executive Offices (green arrow) were "Go in the men's room and take a sharp right." Below shows the relationship between the Executive Car (left) and the office suite. The elevator was accessible from a street entrance, one floor down.

Five years after opening the staff was photographed and numbered five hundred and fifty-six.

They could mix and mingle during the films in the basement cafeteria (top center) located along the long corridor from backstage to front of house.

Because the grid was only forty-five feet higher than the sixty-foot-high proscenium arch, the forty-eight ton fire curtain was constructed in two overlapping steel-framed sections, the upper and lower sections shown in the photo below. "It comes in with a roar...[almost free-falls] and at about twelve feet above the deck, hydraulic plungers slow it," wrote former Chief Projectionist Robert Endres in Cinema Treasures about a "fire drop test."

The "heavy gold satin" drape built in 125% fullness weighed three tons and was lifted by thirteen individually-controlled constant speed motors, preset from the Control Panel. Note the rehearsal table, bottom center.

A back-lit chart on the twelfth row rehearsal table showed the stage lighting positions and their corresponding Rehearsal Letters, starting with A for footlights. Stage director at the Music Hall for forty-two years (and Roxy's successor) Leon Leonidoff is pictured at the table which included a "god mic," invented for Roxy by Western Electric in 1923. Leonidoff, who conceived the Christmas and Easter shows among hundreds, used an ashtray, and the Music Hall had twenty-eight hundred of them, along with fifty-five Watchman's Clocks, eighty-one exits, seven hundred and six mirrors, and thirty-five hundred keys.

A special counterweighted set was provided to facilitate maintenance of the Contour Curtain, which was made up of sections.

This doctored photo illustrates the "Inner Proscenium" a motorized portal that could mask the stage down to the size of a doorway, according to the spec. The border was on a special motorized lineset, and the legs were on sixty-foot-high vertical rolls which tracked at the top. The portal has been long removed, and its lineset location is unknown. It could have been set immediately downstage of the Fire Curtain, as the fire department had allowed a full height traveler downstage of the asbestos at the Music Hall's sister theatre, the Center. The conjectural placement shown below would allow the Contour Curtain to be masked out.

From 1932 until 1979, the Music Hall operated as a Super Deluxe presentation house, premiering a first run picture and a fifty-minute stage spectacle, with a top price of $2.75 to the very end. Four-a-day on weekdays and five on weekends combined to make a thirty-performance-week for the resident orchestra, male glee club, the Rockettes, and the Corps de Ballet, the latter group shown below in "The Undersea Ballet," arguably Leonidoff's best spectacle ever, a permanent fixture in his forty years of rotating repertoire. A new stage show was produced every two to four weeks, depending on the run of the picture.

For at the Music Hall there was a magical Control Panel where one man with a well-aimed finger could do the work of fifty. The panel controlled the thirteen separate devices necessary to play a show and to make the changeover from stage show to picture, and not a single more.

The Control Panel was a one-of-a-kind, and likewise so were its operators, Earl Marshall shown here, the first of four in the history of the Music Hall.

George Ballant, the second operator, circa 1956. The Control Panel will be further examined after a look at the stage.

There were seventy-five eight-line system pipes operated from the Peter Clark locking rail (below), including five travelers, one hundred and eighteen feet wide, with six foot overlaps. Stage weights weighed sixty pounds, but Clark's over-sized overhead underhung loft blocks allowed an empty system pipe to be hauled in by one man.

This photo of double-row K Border (Cyclorama) being fabricated in the Kliegl shop gives an idea the scale of the Music Hall stage. One hundred and forty-four sockets could accommodate two thousand watt lamps behind glass color screens. To read everything about the Music Hall electrics, click here.

Originally the primary sound horns were suspended from a motorized trolley beam, but with the conversion to CinemaScope, the new cabinets were mounted to the back of the Picture Sheet and on E Border. Vertical and horizontal functions for the I-beam trolley, which could clear in fifty-five seconds, were activated from the Control Panel.

A matte shot from the 1942 Hitchcock film "Saboteur" paints a realistic picture of how small picture sheets were before CinemaScope, and the Music Hall was no exception. To the left and right of the stage can be seem the motorized picture sheet traveler known as "the Golds," which got a lot more use than the Contour, which was generally used only at the top and bottom of a show. The Control Panel allowed the Golds four speeds in either direction, slow for the feature and fast for the shorts. Smoking was allowed backstage during shows, but only if the Picture Traveler was closed.

The frame for the CinemaScope picture sheet measured forty-seven by one hundred and seven feet wide and was installed in 1953. Because the Music Hall was the only film theatre still presenting live shows at that time, the frame was made flat, not curved, or otherwise it would occupy too much fly space. The sheet was on a motorized lineset controlled from the Panel, as were the Clark Magnascope controls. The guide cables for the sheet were five inches downstage of Elevator 1, and red warning lights mounted to the underside of this huge Picture Sheet/Horn assembly flashed rapidly when the sheet was in motion.

For the Band Car to work, the multiple Music Hall organ consoles were shunted to a less flamboyant position, placed on motorized cars behind the drapes, circled below. The Band Car also precluded an act lift, a Movietone lift, and lift controls on the conductor stand, standard equipment with Clark's worm-gear jobs.

Generally, the Band Car lived on the pit elevator (left below) and connected electrically via floor pockets on the stage right (control) side. The orchestra pit elevator had four preset stops, numbered "1" to "4" and operated from the Control Panel. The pit, as with the stage lifts, featured automatic deceleration, but the operator could stop the lift at any position and run at any rate of speed. When the lift reached BOTTOM, a Switch Man in the garage would kill power to the elevator at any time that the Band Car was in motion. Similar lockout switches were provided for the stage lifts. To see a larger view, click here.

Below the lift is shown at OVERTURE position, so that the Band Car sits flush with the deck. The advantage of not having a preset button for this level allowed the operator to achieve dramatic impact by shooting the lift upwards from the PRESET position to TOP at a high rate at of speed, then rapidly decelerating right before hitting the target, for a fast and hard stop. Dramatic impact was standard practice at the Music Hall, where four men were required to operate the giant-sized travelers-- two men on the ropes, and two on the leading edges of the drape to ensure a graceful closure.

The New Yorker-- which was never wrong-- credited the Band Car invention to Peter Clark.

But Peter Clark did not invent the Band Car-- it was the brainchild of Jack Partington, a west coast stage director/inventor. Partington also conceived the idea of the "migrating bandwagon" to jazz up his stage shows, which included an on-stage jazz band. A handful of his "Magic Flying Stages " were installed, including in Chicago's Oriental Theatre, where the stage lifts were Partington hydraulic and the pit lifts were Peter Clark worm-gear-- installed at the same time. Jack's greatest contribution was almost immediately adopted by every theatre in the nation: the concept of a "Presentation House" where overtures and preludes were supplanted by fast onstage antics to showcase the picture.

A section view of the stage showing the elevators and also showing the Studio and intermediate level rooms (top right). For a larger view, click here.

Thinking "three-dimensional chess game" might help your understanding of this chart. Start at top right.

The Band Car is shown atop Elevator No. 3 in this fact-filled illustration.

A clever invention allowed Partington's dream to be realized so the orchestra could be heard even from the subbasement. A special traveling cable was made up whereby the output from the newly-invented RCA microphones (left) used on the pit could be paralleled, as shown on the right, and the audio signal never interrupted. Connections were made and unmade by the Band Car Driver and two cable wranglers, concealed by the Band Car back masking. For a larger view of the diagram, click here.

The Music Hall stage was equipped with "54 microphone positions on or above the stage" as shown below. Also shown in yellow are the approximate positions of the traps for the five "disappearing" mics which would rise five foot when activated from the audio booth in the projection room. Installed after the Hall opened, the devices were likely the work of Peter Clark who had invented and installed microphone lifts in the Earl Carroll in 1931.

Cueing was accomplished by buzzing or by a light, activated from the stage managers's desk. A return buzz to a warning would indicate "ready."

The "wood" was wood, and the rest of the stage, battleship linoleum surrounded by gleaming glazed brick. The motorized disappearing footlights could vanish in about twenty-five seconds to make way for the Band Car. When activated, the Steam Curtain shot up a spray of 212 degree Con Ed vapor to make a sort of scrim, the condensation (hopefully) captured in the excelsior-lined trough.

A view of the Band Car Driver during a maintenance session.

Dance numbers were choreographed always placing the Rockettes at least six feet from any vast, open hole.

A 1949 advertisement for Socony Oil showcased the elevators, which were driven not by hydraulic fluid, but by a mixture of water and (Socony) cutting oil, along with an anti-bacterial treatment. Elevator 2 was "the brains of the operation" containing the turntable motor and the electric solenoids which pin ("clutch") the three lifts together to make a turntable.

A view of the pit elevator pit, showing on the left "the island" (which corresponded to the "wood" two floors above) and the Band Car garage to the right. Splitting the island horizontally is the subbasement fire curtain which fills the rectangular opening shown. Beneath the pit lift was a counter-weighted safety railing would sink out of view when the elevator lit upon it. It was stipulated by contract that the orchestra start and finish a performance at this subbasement level, adjacent to their locker and club rooms, but not accessible from the backstage elevators. which terminate on the Shop (basement) level, one long flight above.

A view of the subbasement fire curtain which continues the proscenium fire wall and prevents a stage fire from reaching the house.

The front and back velour masking had not yet been installed in this shot of the underside of Elevator 3. The masking had to be perforated to allow for the escape of air when the lifts entered the lift pit at high velocity. To minimize the dangers of tangled masking, a policy of "last in, first out" was adopted.

It was the speed that could be attained through hydraulics that prompted Clark to make the switch from worm-gear. Worm-gear drives overheat when run fast, and Clark's fastest model ran twenty feet per minute. The Music Hall lifts were designed for a maximum speed of sixty feet per minute, but routine top operating speed was half that: top speed only to compensate for lateness. Each weighed forty-seven tons.

The eleven ton turntable, undergoing routine maintenance, could turn a revolution in fifty-five seconds, or twice that at the Slow position. It could rotate continuously in either direction, a commutator ring supplying juice to its floor pockets.

The stand-alone stage elevators, when fully extended thirteen feet above the stage deck, required some serious stabilization, and this was accomplished by travelling guide rails, equal to the height of the fifty-foot hydraulic pistons, set into tracks and made an inherent part of each lift. Thus four holes were bored for each elevator, two for pistons and two for guide rails, left and right.

The Peter Clark lifts at the Music Hall were the first hydraulic stage elevators to be electrically controlled, and besides serving the stabilizer function, the solid steel guide rails were also the key to Clark's equalizer system. The teeth (rack) in the guides would mesh with the pinion gear of the equalizer (inset), and via a stage-width equalizer shaft would lock and synchronize the two sides of the elevator together. When the lifts moved, the shafts spun, motivating an electrical servo switch switch mechanism which told the Control Panel the actual height of a given elevator. "Peter Clark Inc." and patent number 1,922,525 were integrally cast within the the base of the equalizer gear (right) and on the piston casings.

Original hydraulic engineer Bill Kells is on duty in the pit where pneumatic pressure activated the clutches which could lock the three equalizer shafts together, necessary to enable the turntable. The elevator pit, a level below the subbasement, was the engineer's battle station during a performance, where he "greased the pistons" both literally and figuratively. When the lifts were not in use, and the Control Panel Lift Stop switches turned downwards, the engineer would close a single valve on each of the four elevators, effectively locking the lifts in place at stage level. Then the system could be turned off.

A controller panel for each lift and turntable were located beneath "the island" in the Hydraulic Equipment Room.

Framed in green, the brass and bronze Peter Clark Control Panel was located stage right, immediately offstage of the stage manager's desk. Actual Position Indicators of the Contour Curtain (left) were mechanically activated by small steel cables which ran all the way up to the associated hoist motor in the grid. Speed Clutch push buttons with key faces were located beneath the speed regulators (right center) and served to mechanically lock the three speed regulator dials together. The legend at the bottom of the panel read: "When elevators are operated from Master buttons, speed clutches should be pushed in."

The Lift Stop switch was normally set to the up or go position when the lifts were in use, because it activated the automatic inching. To select a target, the operator would (1) turn off the Lift Stop switch; (2) press the momentary Up or Down selector buttons or flip the Selector Stop switch upwards, making the selector run constant; (3) once a target was set, the operator would turn on the Lift Stop switch; and then (4) he would press Lift Starting, which started the lift. Because the fastest selector speed was only about thirty feet per minute, to make tight cues the operator "chased the selector," activating an elevator while the selector was still hunting.

Two sliders at the bottom of the Control Panel controlled the Inner Proscenium.

While the picture unreeled, a stagehand was assigned to the Control Panel as "stage watch." If the film broke, he would close "the Golds" and activate emergency Houselights. He was to keep a sharp eye on Elevator 1, because if it drifted upwards on its own, it would crush the massive Picture Sheet. In this event, he would hit Emergency Stop and telephone the engineer.

Eighty-eight years after installation, Music Hall insiders describe the Peter Clark hydraulics as "very reliable," stagehand slang for perfect.

The New York World-Telegram wrote: "A galaxy of stars might be stricken from the bills without creating the actual void on Broadway caused by the death of Peter Clark."

As a fitting climax, click here to view a short video showing the Control Panel in action. Operator Eric Titcomb is at the controls for the 1998 Christmas show, when the Clark stage systems had been in continuous service for sixty-five years.

Bob Foreman (author) spent his career restoring old theatres and is a long-time member of IATSE and an ESTA-certified theatre rigger.

June 2020

It was the speed that could be attained through hydraulics that prompted Clark to make the switch from worm-gear. Worm-gear drives overheat when run fast, and Clark's fastest model ran twenty feet per minute. The Music Hall lifts were designed for a maximum speed of sixty feet per minute, but routine top operating speed was half that: top speed only to compensate for lateness. Each weighed forty-seven tons.

The eleven ton turntable, undergoing routine maintenance, could turn a revolution in fifty-five seconds, or twice that at the Slow position. It could rotate continuously in either direction, a commutator ring supplying juice to its floor pockets.

The stand-alone stage elevators, when fully extended thirteen feet above the stage deck, required some serious stabilization, and this was accomplished by travelling guide rails, equal to the height of the fifty-foot hydraulic pistons, set into tracks and made an inherent part of each lift. Thus four holes were bored for each elevator, two for pistons and two for guide rails, left and right.

The Peter Clark lifts at the Music Hall were the first hydraulic stage elevators to be electrically controlled, and besides serving the stabilizer function, the solid steel guide rails were also the key to Clark's equalizer system. The teeth (rack) in the guides would mesh with the pinion gear of the equalizer (inset), and via a stage-width equalizer shaft would lock and synchronize the two sides of the elevator together. When the lifts moved, the shafts spun, motivating an electrical servo switch switch mechanism which told the Control Panel the actual height of a given elevator. "Peter Clark Inc." and patent number 1,922,525 were integrally cast within the the base of the equalizer gear (right) and on the piston casings.

Original hydraulic engineer Bill Kells is on duty in the pit where pneumatic pressure activated the clutches which could lock the three equalizer shafts together, necessary to enable the turntable. The elevator pit, a level below the subbasement, was the engineer's battle station during a performance, where he "greased the pistons" both literally and figuratively. When the lifts were not in use, and the Control Panel Lift Stop switches turned downwards, the engineer would close a single valve on each of the four elevators, effectively locking the lifts in place at stage level. Then the system could be turned off.

A controller panel for each lift and turntable were located beneath "the island" in the Hydraulic Equipment Room.

Framed in green, the brass and bronze Peter Clark Control Panel was located stage right, immediately offstage of the stage manager's desk. Actual Position Indicators of the Contour Curtain (left) were mechanically activated by small steel cables which ran all the way up to the associated hoist motor in the grid. Speed Clutch push buttons with key faces were located beneath the speed regulators (right center) and served to mechanically lock the three speed regulator dials together. The legend at the bottom of the panel read: "When elevators are operated from Master buttons, speed clutches should be pushed in."

Two sliders at the bottom of the Control Panel controlled the Inner Proscenium.

While the picture unreeled, a stagehand was assigned to the Control Panel as "stage watch." If the film broke, he would close "the Golds" and activate emergency Houselights. He was to keep a sharp eye on Elevator 1, because if it drifted upwards on its own, it would crush the massive Picture Sheet. In this event, he would hit Emergency Stop and telephone the engineer.

Eighty-eight years after installation, Music Hall insiders describe the Peter Clark hydraulics as "very reliable," stagehand slang for perfect.

The New York World-Telegram wrote: "A galaxy of stars might be stricken from the bills without creating the actual void on Broadway caused by the death of Peter Clark."

As a fitting climax, click here to view a short video showing the Control Panel in action. Operator Eric Titcomb is at the controls for the 1998 Christmas show, when the Clark stage systems had been in continuous service for sixty-five years.

###

For a master index of all of Bob Foreman's photo-essays, click here.

This article is available in printed format, having been serialized over three issues of Theatre Organ Journal, November 2020 to March 2021. To purchase these issues, click here.

For HD views of selected photos, click here.

For HD views of selected drawings, click here.

To see all of Peter Clark advertisements and a detailed look at his counterweight system, click here.

To see all of Peter Clark advertisements and a detailed look at his counterweight system, click here.

Acknowledgements and Notes

Special thanks to Duncan MacKenzie, Michael Zande, Bill Counter, and Rick Zimmerman for their invaluable contribution to this effort.

Others who deserve mention are, in alphabetical order, Giovanni Angotti, Winston Atkins, Rick Boychuk, Tommy Brent, Tim Burns, John Calhoun (NYPL--Billy Rose), John Cardoni, Cinema Treasures, Peter Clark (Met Opera Archivist), Ryan Cole, Dennis Degan, Mitch Deutsch, George Dummitt, Bobby Ellerbee, Don Feely, Karen Fischer, Mary Foreman, Marty Fuller, Rory Grennan, Ben Hall, Scott Hardin, Alison Harper, Don Hoffend, Jr., Don Hoffend, Sr., Diane Jaust, Blake Joblin, Brad Joblin, Jimmy Keane, Wade Laboissionniere, Ken Lager, Alexandria Lang, LANTERN, Bruce Laverty, Carlos Martinez, John McCall, Joe Mobilia, Garry Motter, MSG Entertainment, Daniel Okrent, Joe Patten, Lisa Lacroce Patterson, the Peter Clark family, Mack Reed, Tom Rinaldi, Ken Roe, Christine Roussel, Joel Rubin, Scott Scheidt, Patrick Seymour, Ray Spurlin, Olaf Soot, Richard Streeter, John Tanner, Eric Titcomb, Nicholas Van Hoogstraten, Luci Waldron, Wendy Waszut-Barrett, and Dave Winslow.

Bibliography

The best book about Movie Palaces is Ben Hall's "The Best Remaining Seats," 1961. Below, books and articles by date.

Special thanks to Duncan MacKenzie, Michael Zande, Bill Counter, and Rick Zimmerman for their invaluable contribution to this effort.

Others who deserve mention are, in alphabetical order, Giovanni Angotti, Winston Atkins, Rick Boychuk, Tommy Brent, Tim Burns, John Calhoun (NYPL--Billy Rose), John Cardoni, Cinema Treasures, Peter Clark (Met Opera Archivist), Ryan Cole, Dennis Degan, Mitch Deutsch, George Dummitt, Bobby Ellerbee, Don Feely, Karen Fischer, Mary Foreman, Marty Fuller, Rory Grennan, Ben Hall, Scott Hardin, Alison Harper, Don Hoffend, Jr., Don Hoffend, Sr., Diane Jaust, Blake Joblin, Brad Joblin, Jimmy Keane, Wade Laboissionniere, Ken Lager, Alexandria Lang, LANTERN, Bruce Laverty, Carlos Martinez, John McCall, Joe Mobilia, Garry Motter, MSG Entertainment, Daniel Okrent, Joe Patten, Lisa Lacroce Patterson, the Peter Clark family, Mack Reed, Tom Rinaldi, Ken Roe, Christine Roussel, Joel Rubin, Scott Scheidt, Patrick Seymour, Ray Spurlin, Olaf Soot, Richard Streeter, John Tanner, Eric Titcomb, Nicholas Van Hoogstraten, Luci Waldron, Wendy Waszut-Barrett, and Dave Winslow.

Bibliography

The best book about Movie Palaces is Ben Hall's "The Best Remaining Seats," 1961. Below, books and articles by date.

| 1927 | Book | R.W. Sexton | American Theatres of Today |

| 1930 | March | Popular Science | Radio City to cost $250,000,000 |

| 1930 | May | Architectural Record | Procedure in Designing a Theatre |

| 1931 | July 17 | Yonkers Herald | Otis Co. May Make Radio City Lifts |

| 1932 | April | Architectural Forum | V. The International Music Hall |

| 1932 | April | Architectural Forum | VI. Structural Frame of the International Music Hall |

| 1932 | June | Architectural Record | Theatre Designs for Rockefeller Center |

| 1932 | July | Popular Mechanics | Orchestra Platform on Elevators and Track |

| 1932 | August | Popular Mechanics | World's Largest Theatre… |

| 1932 | November | Theatre Arts | Building Number 10. |

| 1932 | December 12 | Variety | Stage Lighting, etc. |

| 1932 | no date | Kleigl Brothers Brochure | Lighting the World's Greatest Theatres |

| 1932 | September | Architectural Forum | Behind the Scenes (by Peter Clark) |

| 1933 | February | Popular Science | World's Biggest Stage is Marvel of Mechanics |

| 1933 | February | Popular Mechanics | The Greatest Theatre in the World |

| 1933 | March | Popular Mechanics | A Modern Tower of Babel |

| 1933 | March | Scientific American | An Entertainment Treasure House |

| 1933 | September | Journal of the SMPE | Radio City Sound Equipment |

| 1933 | August 8 | Electrical World | Refinement in Controls at Radio City… |

| 1936 | February | Steel | Stage in Radio City Music Hall… |

| 1937 | June | Modern Machine Shop | Hydraulic Power and it Applications to… |

| 1937 | December 29 | Motion Picture Daily | Radio City Fifty Anniversary Issue |

| 1937 | no date | Radio City | Radio City Pictorial |

| 1940 | December 2 | Life | Rockette No. 33 |

| 1941 | January | Popular Mechanics | Secrets of the "Magic" Theatre |

| 1943 | April 26 | Life | Radio City Music Hall |

| 1944 | April 22 | Showmen's Trade Review | Radio City Music Hall -- Climax of Fifty Years… |

| 1946 | Book | William Peck Banning | Commercial Broadcast Pioneer (WEAF and Roxy) |

| 1949 | April | Coronet | Maestro of the Music Hall |

| 1949 | Book | Harold Burris-Meyer | Theatres and Auditoriums |

| 1950 | April | Popular Mechanics | Hall of a Thousand Illusions |

| 1955 | no date | Joseph Vasconcellos | Catalog (successors to Peter Clark) |

| 1961 | Book | Ben Hall | The Best Remaining Seats |

| 1964 | December 11 | Life | The Rockettes |

| 1966 | Book | Ben Hall | Radio City Music Hall Souvenir Program |

| 1973 | Book | William C. Young | Documents of the American Theatre |

| 1974 | October | Theatre Crafts | Radio City |

| 1979 | Book | Francisco, Charles | The Radio City Music Hall |

| 1979 | Book | David Naylor | American Picture Palaces |

| 1980 | Book | Judith Anne Love | Thirty Thousand Kicks |

| 1991 | Book | Nicholas Van Hoogstraten | Lost Broadway Theatres |

| 1999 | Third Quarter | Marquee | Radio City Music Hall (by Lyman Brenneman) |

| 2000 | April | Preservation News | Backstage at Radio City |

| 2003 | Book | Daniel Okrent | Great Fortune |

| 2005 | Winter | Spotlight (IATSE Local One) | Local One Continues the Tradition at Radio City's… |

| 2012 | Book | Ross Melnick | American Showman (Roxy) |

| 2017 | December | American Theatre | Hemp Houses: Know the Ropes |

June 2020

.jpg)